Anyone interested in the antecedents of the Egyptian civilisation and the cultures that predated the unification of the country under one king may soon have many of their questions answered. Items showing evidence of the activities of the early peoples of the Nile Valley, from the predynastic cultures of Upper and Lower Egypt, Fayoum and the oases of Siwa and Kharga selected from storehouses around the country, plus pieces from various museums, will soon be on display in a new predynastic museum at Qena.

The museum is currently being built at an ideal location -- a prominent five-feddan site overlooking the Nile. Mahmoud Mabrouk, head of the museums sector of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), which is overseeing the work, says it will represent a long period of history covering about 10,000 years. He adds that a plan has already been worked out to start surveying and registering predynastic items in order to prepare a database of antiquities.

The museum is currently being built at an ideal location -- a prominent five-feddan site overlooking the Nile. Mahmoud Mabrouk, head of the museums sector of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), which is overseeing the work, says it will represent a long period of history covering about 10,000 years. He adds that a plan has already been worked out to start surveying and registering predynastic items in order to prepare a database of antiquities.

As were other parts of the world, Egypt was occupied by Stone Age hunting, fishing and food-gathering communities in the Late Paleolithic. In about 5000 BC, Neolithic or New Stone Age people wandered along the river terraces of the Nile Valley, and traces of their agricultural, hunting and animal domestication activities have been found on numerous sites. Interestingly, from very early times many of the artefacts produced had a peculiarly "Egyptian" character, and their styles continued through various development phases well into the early historical period.

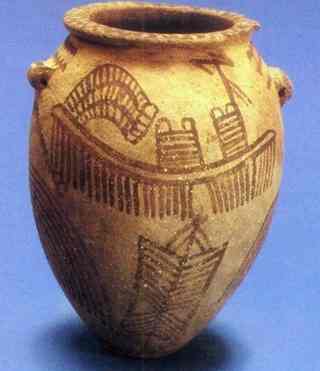

The work on predynastic sites, discovered independently by Britain's Flinders Petrie and France's Jacques de Morgan in the late 19th century have now been expanded. Literature has become specialised and scattered, and the sources and types of material, in the absence of a written language, remain wide-ranging and complex. Take pottery for example. It was used for vessels which served a wide variety of functions long before the first Pharaohs -- for everyday cooking and domestic purposes, storage of cosmetics and oils, for the transportation of food and drink, and funerary rituals. There were also fancy vessels in the form of humans, animals and birds, decorated vessels, and mother- goddess figures. The historical development of Egyptian pottery alone, and its role in Egyptology, is extremely complex.

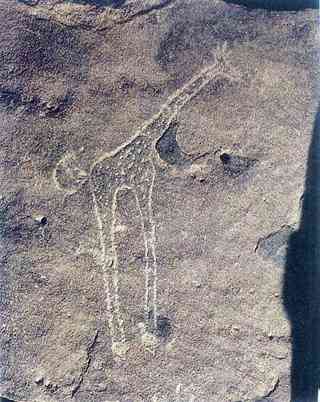

What do predynastic objects tell us about the inception of Egyptian culture? What do flint tools, stone mace heads, chisels and adzes, metal jewellery, slate cosmetic palettes, leather and textile clothes and containers tell us about society? Were small objects in ivory, stone, shell and faience depicting zoomorphic figures actually representations of deities? Were they devices to ward off evil? And to what extent do they reveal a complex and developing community, its class structure, its organisation? Were goods created for trade? Were luxury items and minerals unobtainable locally and therefore imported into the country?

What do predynastic objects tell us about the inception of Egyptian culture? What do flint tools, stone mace heads, chisels and adzes, metal jewellery, slate cosmetic palettes, leather and textile clothes and containers tell us about society? Were small objects in ivory, stone, shell and faience depicting zoomorphic figures actually representations of deities? Were they devices to ward off evil? And to what extent do they reveal a complex and developing community, its class structure, its organisation? Were goods created for trade? Were luxury items and minerals unobtainable locally and therefore imported into the country?

These are but a few of the questions raised by scholars of various specialisations, and the predynastic sites so far excavated -- both settlement sites and cemeteries -- reveal a truly remarkable picture. Since the early days of study, radiocarbon dating has been refined and the methods used today are more sensitive and accurate. Hair, skin, shell and wood samples can now be tested with accuracy. It is no longer necessary to identify foreign imports on stylistic grounds alone when analysis can prove or disprove an argument. Remnants of clothing in some predynastic sites show that the people wore kilts, sometimes with decorative girdles, and feathered headgear. Strings of blue-glazed beads, anklets of shells and bracelets of ivory attest to the standard of personal decoration, as do oval slate palettes which bear traces of red ochre or green malachite probably used to grind body or face paint.

The earliest known "seasonal settlements" in Egypt are in Fayoum, the depression in the Western Desert that was filled by the Nile in about 8000 BC to create a considerable lake with a much higher water level than it has today. Mud huts were built on mounds along its north and north-east shores when the level of the lake gradually fell and where the land was fertile, and by about 5000 BC emmer, wheat, barley and flax were being cultivated and harvested using sickle-flints set in wooden handles. Traces of cloth reveal that the people wove linen, which they probably wore beneath an outer garment of leather. Stone beads and pendants show that they also developed drilling techniques. Pottery was made of coarse clay and fashioned in a variety of shapes. This seasonal, semi-nomadic existence where, despite an increase in animal husbandry, expeditions into the desert to hunt large mammals continued. Such an existence can also be traced at many sites in Upper Egypt south of Assiut where, although the actual settlements built on levees along the banks of the river have long disappeared, burial grounds provide evidence of early society. Ivory spoons, figurines, and small copper objects -- hammered, not cast -- were among the grave goods.

The earliest evidence of fully sedentary village life can be found at Merimda, a sandy rise in the Western Desert on the edge of the Delta near the Rosetta branch of the Nile. Radiocarbon readings reveal evidence of occupation from 4440 to 4145 BC, and some scholars suggest an even earlier date. Groups of small, flimsy huts made of wicker were built on spurs, and it is thought that they may have been used for much the same purpose as in rural communities in Egypt until today for storing food and tools rather than for habitation. Such lightly constructed shelters may have also provided shade for workshops and cooking areas.

The predynastic period is an exciting field of study. Early Egyptologists tended to discard fragments of pottery, ostrich shells and bones. Today we know their importance in revealing different stages of settlement, dietary habits and social patterns of the earliest people who settled in the Nile Valley, whether farmers or stock-breeders who raised cattle, sheep, goats and pigs, and who, over the passage of time developed trading centres in major settlement areas. One such predynastic settlement area shows that the inhabitants were indeed traders. I refer particularly to the contents of the delightful and little-known and long neglected dig-house, known as the Maadi Museum, the contents of which will take prime place in the new predynastic Qena Museum.

Maadi's strategic position in pre-history is not widely known, yet it is unique. It was first excavated in 1918 and the results were made public in a report to the International Congress of Geography in 1925. Three years later, the famed Egyptologist J Lucas visited the site and identified three specific areas of the settlement. His observations ignited further interest and, in 1929, he decided to initiate a project for its investigation. Eleven archaeological missions were carried out there under the directorship of various Egyptian and foreign pre- historians, but unfortunately the mission came abruptly to an end with the outbreak of World War II -- although luckily not before the research resulted in the publication of four volumes of detailed studies carried out by specialists in the fields of natural sciences, pottery, lithic industries, non-lithic objects and cemeteries. It is, so far, the most comprehensive and well-documented pre-dynastic objects in the whole of Egypt.

Maadi's strategic position in pre-history is not widely known, yet it is unique. It was first excavated in 1918 and the results were made public in a report to the International Congress of Geography in 1925. Three years later, the famed Egyptologist J Lucas visited the site and identified three specific areas of the settlement. His observations ignited further interest and, in 1929, he decided to initiate a project for its investigation. Eleven archaeological missions were carried out there under the directorship of various Egyptian and foreign pre- historians, but unfortunately the mission came abruptly to an end with the outbreak of World War II -- although luckily not before the research resulted in the publication of four volumes of detailed studies carried out by specialists in the fields of natural sciences, pottery, lithic industries, non-lithic objects and cemeteries. It is, so far, the most comprehensive and well-documented pre-dynastic objects in the whole of Egypt.

Little remains of the actual site today. It continues to be seriously threatened by further urban expansion, visibly creeping up on the ancient dig-house and its valuable collection which, fortunately, will be transferred to the Qena Museum in due course. I remember visiting the site 10 years ago, in late November 2000, when the late Ibrahim Rizkana was custodian. He told me about the excavations and the fact that Maadi was ideally located for contacts with Upper and Lower Egypt, as well as with western Asia through a wadi leading to the Isthmus of Suez. He explained how the "Maadians" benefited from trade, being well placed with plenty of drinking water and situated as it was on a terrace at the fringe of the desert safe from high floods. The number of graves found in the cemeteries suggested a large community, believed to be traders who lived in a "real town", and produced a number of innovations in around 4000 BC. It was not, according to Rizkana, a simple trading post, but a settled community where the people practised agriculture, bred animals, wove fabrics, used teeth and shells for ornaments, made bread and manufactured stone vases and pottery jars for storage. The excavation of distinctive imported Palestinian pottery aroused the interest of scholars as soon as the preliminary reports appeared.

It is now pretty certain that Maadi's pre- dynastic site, which is a more elaborate and complex settlement than the pre-dynastic sites of Lower Egypt, will feature strongly in the new museum. It will be revealed that the people had a variety of rectangular houses, oval huts, subterranean shelters, storage pits and sunken storage jars. Interestingly, the houses and huts were concentrated in the centre of the settlement, while the storage facilities were around its edge. Burials, except for infants, were in cemeteries away from the settlement.

The subterranean "houses" proved to be the most interesting of all. The three that were found were dug about two metres deep and in various shapes. Some appear to have been domed and covered with matting, a practice not common in Egypt but found at several sites in southern Palestine. This suggested to some of the archaeologists who excavated the site that they were actually the houses of foreigners in Maadi. Rizkana, however, thought that idea "rather farfetched", and said they were more likely to have been for common use, perhaps for administrative purposes. His thoughts about the settlement were, I recall, somewhat contradictory. He admitted that the Maadi settlement might have been a sort of shantytown, a trade station for various goods, but then on other occasions he said that it could have been a real town occupied by people with innovative ideas. Why, he postulated, was there an absence of threshing and harvesting implements, while grinding stones could be counted in their hundreds? And why, of the nearly 100,000 stone implements discovered were there only a dozen stickles and a handful of axes?

Mysteries always pique interest and although, as mentioned above, very little remains of the pre-dynastic site for further excavation, a new study of the objects -- once they are placed in a new setting and considered alongside the already published literature -- might enable modern scholars to answer some old scholarly questions.

The new museum at Qena, devoted to predynastic objects of all periods, will be a valuable source of information covering a field that is rapidly expanding and increasingly capturing the interest of travellers and the lay public as well as scholars.

Source: Al Ahram Weekly

VIA «A new look at Prehistory»